O I forbid you, maidens a’,

That wear gowd on your hair,

To come or gae by Carterhaugh,

For young Tam Lin is there.

– opening verse of Tam Lin, Child Ballad 39a

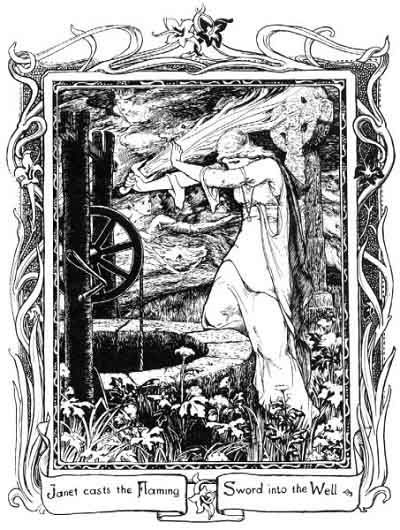

Thus begins the beloved Scottish faery ballad, “Tam Lin,” first recorded in 1549 in The Complaynt of Scotland. “Tam Lin” tells the story of a young girl named Janet, who ignores the advice of the opening stanzas and runs away to Carterhaugh, where she is impregnated by the titular elf lord haunting the woods. Later, Janet returns and asks Tam Lin whether he is a mortal; he tells her that he is but is being held captive by the Queen of Faery. Tam Lin suspects he is intended to be the sacrifice, or teind, which Faery pays to Hell every seven years. But if Janet loves him, she can save him. She must wait at Miles Cross on Halloween, when the faeries go trooping by, and pull him from his horse. Holding him tight while he transforms into several dangerous beasts and finally into a burning brand or coal, she must throw into the well then cover the now naked, but human Tam Lin with her mantle, thus freeing him from Faery’s influence. Against all odds, Janet clings to her lover through all his transformations, thus saving him. The Faery Queen curses her “ill-far’d face,” wishing she had torn out Tam Lin’s heart and/or eyes so this betrayal would never have happened.

I have been obsessed with the ballad of Tam Lin for over thirty years now, ever since I read Diana Wynne Jones’s fabulous book Fire and Hemlock. In fact, this obsession led directly to the writing of my debut novel, THE CHANGELING QUEEN, a reimagining of Tam Lin from the Faery Queen’s point of view.

One of the reasons I love Tam Lin is the heroine’s sense of agency: the girl gets to do the rescuing for once. I love that Janet is disobedient, headstrong, and determined to bear her child (or not) on her own terms, rather than meekly agreeing to let her father marry her off to one of his knights. For these reasons, as old as the ballad is, it is ripe for the retelling in 2025. “Tam Lin” resists slut shaming, treats the topic of bodily autonomy with respect and without judgment, and, if we read between the lines, has much to tell us about the connection of female agency to social class as well. These are the themes I have chosen to focus on in THE CHANGELING QUEEN and can only hope that I have done so half as well.

At the beginning of the ballad, as noted above, young maidens are warned away from the woods of Carterhaugh, where Tam Lin resides. If they go there, he will demand from them their cloaks, their rings, or else their maidenhead. Nevertheless, Janet braids back her hair, hitches up her skirts, and runs away to Carterhaugh as fast as she can go. I must say, I like her gumption; this is hardly the behavior one might expect of, say Cinderella or Snow White, or many another folkloric maid whose obedience to authority might be held up as an example. She’s not even a Pandora or Bluebeard’s wife, who at least made a show of resisting the pull of curiosity at first. No, Janet not only ignores the advice, but heads off to meet the elf lord in a green kirtle, no less, the color beloved of the fairies. It is almost as if she knows full well what she is getting into! She catches his attention by plucking a rose, which brings on a rather flirty exchange over who owns the rights to Carterhaugh, and she runs off to her father’s hall afterwards, pregnant.

If it seems like I have skipped a few steps here, that is because many versions of the ballad skip those very steps. We only learn that Janet is pregnant when she returns to her father’s hall, “as green as any glass,” and an elderly knight says that they, her father’s knights, will be blamed for her condition. It is an interesting objection he makes, for he doesn’t so much call Janet’s virtue into question, does not insult or call her names, simply fears he and his comrades might get in trouble for what Janet has done. And Janet’s father scarcely reprimands her, either:

Out then spak her father dear,

And he spak meek and mild,

“And ever alas, sweet Janet,” he says,

“I think thou gaest wi child.”.

His tone is tinged with slight regret, but rather less blame than we might expect. The pregnancy is simply a matter than must be dealt with, most likely by marrying her off. We might find this attitude surprising in such a patriarchal society as medieval or early modern Scotland. But under the custom of handfasting, consummation might precede formal marriage, and in Scotland in particular common law marriage persisted through the 17th century. I would also note that Janet’s birth gives her some privilege; her father owns a castle and has many knights, who could presumably be convinced to marry her with sufficient dowry, promise of land, or even force. The ballad does not concern itself with what might happen to Tam Lin’s lovers of lesser means, the very ones who could not buy him off with a ring or a cloak, who even if they managed to save his life might be found an unsuitable partner for the nobly born Tam Lin. It’s a story that speaks of female agency and bodily autonomy, but it does not address the harsh realities of single motherhood among women of lesser means.

But privileged or not, Janet is unwilling to enter a loveless marriage for the sake of her unborn child. She tells her father:

“If that I gae wi child, father,

Mysel maun bear the blame,

There’s neer a laird about your ha,

Shall get the bairn’s name.”

Instead, believing Tam Lin an elf lord whom she cannot marry, Janet returns to Carterhaugh, in many versions to terminate her pregnancy. And again, we find little condemnation of Janet’s behavior, and while it might be tempting, as we read on, to say, “Well, she didn’t do it after all, did she? That’s why there’s no reproach,” I don’t think that’s it. She gathers an herbal abortifacient–in THE CHANGELING QUEEN, I go with pennyroyal, which has been used for this purpose since at least Aristophanes’ time. Yes, abortion was known in ancient and medieval times, and even the Catholic Church once considered it acceptable if it came before the point of quickening.

Janet doesn’t choose to keep her child because she feels guilty; rather, she confronts Tam Lin about his parentage and discovers he is a Christian and thus a worthy father for her child. She follows his instructions, journeys to Miles Cross at the “mirk and midnight hour,” pulls him from his horse, holds him despite his many dangerous transformations, and finally throws him into the well, when he emerges as a naked man. All’s well that ends well. A model of female agency for our time.

This is of course a very modern reading of the ballad. The heroine of THE CHANGELING QUEEN is “Tam Lin’s” foe, who also sees things, if not through a modern lens, at least with an outsider’s eyes. She is not a human, not fully, though she grows up in the guise of a peasant woman in medieval Scotland. Known only as Bess Grieve, my heroine is torn between the values of the mortals she grew up among and the faery world she truly belongs to. In Faery, there is no shame in lovemaking, ever; fertility is rare, and if one expects that might influence the Queen’s thoughts on abortion, well, my heroine starts her life as a midwife’s daughter who understands how desperate an unwed mother might be.

My novel is both a continuation and prequel to “Tam Lin,” as the Queen narrates her life story to Janet and Tam Lin. I want to celebrate all the wonder, beauty, and danger of the original ballad, and its heroine’s courage, self-determination, and fight for bodily autonomy throughout the tale. Yet THE CHANGELING QUEEN also holds a mirror up to “Tam Lin”, just as my faery queen forces Janet to confront examples of less privileged women who could not escape single motherhood the way she did, and who suffer greatly for it. My aim is to take the empowerment of the original ballad and expand it, revealing how patriarchy hurts everyone, that compassion has no religion, and that sometimes we all must make the most heartbreaking sacrifices for our own self-preservation. But if all my novel does is convince more readers to investigate this ancient ballad and see how truly ahead of its time it was, I will be more than content.

Blogger’s note: All references have been taken from Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Dover Publications, 1965, 39a. For more information, please see the wonderful website http://www.tam-lin.org.